Friday, January 20, 2017

Respect and Respectability: Russell Moore vs. Mel Gibson

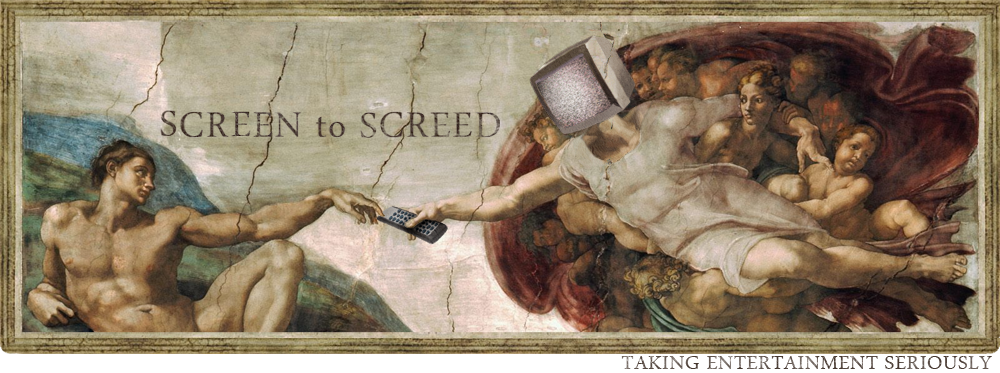

Since the sexual revolution destroyed Christian hegemony over American culture, the deposed have been debating the appropriate manner of engaging a post-Christian culture. The initial televangelist-led counter-counterculture, epitomized by the late Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority and Pat Robertson's CBN, favored straightforward, direct engagement. But a counter-culture headed by a federation of rotund cheeseball preachers and politicians proved to be no match for the Left's slick culture war machine. Though they would go on to notch further political victories, their ultimate cultural failure became evident when Bill Clinton's already strong approval ratings spiked as high as 68% after the Lewinsky imbroglio. As the culture war defeats have since accelerated in number and severity, two rival approaches to cultural engagement have emerged as candidates to lead the Christian counter-culture out of the wilderness. The clearest way to distinguish these approaches is through their differing goals: respect and respectability.

Respectability

The respectable side is best exemplified by Russell Moore, author of Onward: Engaging the Culture Without Losing the Gospel and President of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission for the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). As a Southern Baptist preacher, Moore shares a church and a vocation with Falwell, Robertson and a host of other Religious Righters. Indeed, the ERLC is something of a remnant of the Religious Right organizations of yesteryear – it emerged out of conservative revolution in the SBC that defunded its left-leaning predecessor, the Baptist Joint Committee run by liberal minister James Dunn. In his manifesto Onward, Moore breaks from both traditions, at once scorning the erstwhile Religious Right for its worldliness and rejecting the nominally Christian Left's flight from fundamentalism.

This approach shares much in common with the Benedict Option touted by American Conservative editor Rod Dreher - both welcome (or at least embrace the silver lining of) defeat in the culture wars as a means of returning to the celebrated anti-materialist purity of the early church martyrs and the various silos of Christianity that held out against tremendous pressure from the secular West. Yet, as his title suggests, Moore doesn't share Dreher's inward-looking, anti-modern monasticism. To the contrary, he wholeheartedly embraces a global Church identity, one that eagerly piggybacks on secular global crusades for civil rights and immigration reform while intentionally remaining a "prophetic minority" in the domestic sphere.

Like many utopian visions, Moore's approach is riddled with magical thinking, oversights and inconsistencies. Moore either does not recognize or acknowledge that his secular globalist allies in the fight against the old standbys of racism and nativism view his positions on abortion and, especially, homosexuality as monstrous and repressive. Thus while he rails against the idea of a Moral Minority stretching for a Majority by including prosperity-preaching televangelists, fire-breathing Mormon talk show hosts (ironically, Moore found himself arm-in-arm with Glenn Beck as part of National Review's Against Trump coalition) and "serially-monogamous casino magnates", i.e. Trump, he has no problem reaching across the aisle in the other direction. Hence his courtship of Black Lives Matter, his advocacy for admitting Muslim refugees and his repeated affirmations of the Left's judgement of 1950's America as a morass of materialism, sexism, racism and bigotry.

Viewed as a whole, Moore's manifesto is as full of holes as the "Seamless Garment" pushed by left-leaning Catholics. The Seamless Garment aimed to tie abortion seamlessly into a holistic platform opposing all injustice. In effect the Seamless Garment was, as John Zmirak argues, an attempt at "saddling the pro-life movement with a deadly poison pill: Either embrace our outrageous, implausible, and likely suicidal utopianism, or let us go on murdering a million children per year." Thus the real utility of the Seamless Garment was not in advancing the actual causes it espoused, utopian or otherwise, but in providing cover from criticism from the left and right.

Viewed from this lens, Moore's argument can be reduced to a plea for respectability. Wielding his Christian fundamentalism within SBC circles, Moore can disarm challenges from the grassroots conservatives in ways that an outright liberal like James Dunn could not. When calls for his head came in the wake of Trump's victory, a host of conservatives rushed to his defense, including Dreher. He was only extrapolating from fundamental Christian principles you see. Then when engaging with the leftist establishment in DC and major media outlets like the Washington Post and the NY Times, Moore can present a huge swathe of his most left-friendly extrapolations. Their favorite Moore trick? Lecturing "angry white men" in the Bible Belt for being farther removed from "Middle Eastern illegal immigrant" Jesus than the third world refugees and immigrants they want to keep out of the country.

This approach has undoubtedly won Moore a kind of respectability. The establishment press, always leery of handing over the megaphone to fundamentalist Christians, proved extraordinarily open to his message. In the run-up to the election, he scored op-eds at the Post and Times along with a steady supply of attentive ears in interviews, culminating in an admiring, novella-size profile in the New Yorker the day before the election. The triumphal title - "The New Evangelical Moral Minority" - was by no means one sided: the magazine of the liberal elite was joining hand in hand with Moore and a new wave of Evangelicals to celebrate the political marginalization of American Christianity.

As the sharks circling Moore's island fortress at the ERLC attest, there are many outraged by the ascendance of his respectability-driven model. But the return of a Moral Majority style offensive spearheaded by televangelists and megachurchers seems unlikely. While Moore's diagnosis of a collapsing Bible Belt is premature, and his prescription of an army of hip, tattooed young pastors passionate about prison reform is as ridiculous and painfully naive* as Howard Schultz's pie-eyed "Race Together" stunt, it's hard to get excited about a return to Pat Robertson. To borrow from the infomercial, the televangelist's secular cousin, there must be a better way!

Respect

One might be tempted to see in Trump's victory a broader return of 80's-style ostentation complete with larger-than-life Evangelical leadership - call it Bakker to the Future. But a notable subplot in the primary mania was the stubborn ceiling of support for Ted Cruz, an Elmer Gantry par excellence, even among Southern Evangelicals. Trump's primary victory was not because he was the Swaggart to Cruz' Falwell (Moore's analogy - his South-centric analysis extended to dub Rubio Billy Graham), but because he was the wildly irreverent Peter Venkman to a host of sanctimonious bureaucrats. Trump laid an independent if morally tainted claim to respect based solely on his own brand and body of work, blithely dismissing the self-appointed gatekeepers of respectability ennobled and emulated by Moore.

The Bible Belt was willing to look beyond its own waistline and recruit a geographic and cultural outsider to tackle its political agenda in Trump. There is now an appreciable hunger for a champion with a similarly independent claim to American respect to continue the counter-revolution throughout the rest of the culture. As the charisma of Southern Baptist preachers tends not to translate outside their own region, the goal is to recruit from within the decadent post-Christian culture, to intercept a talented enemy on his way to Damascus and win, or at least steer him to the cause. Such was the case with Trump - the once liberal and still decadent New Yorker - and is likely to be the case for his cultural counterpart(s).

Such a Christian counter-culture leader has already been active for most of the new millennium, albeit unwittingly and probably unwillingly. I speak of Mel Gibson. He'd hardly recognize himself as such. His public pronouncements range wildly between affirmations of ultraconservative Roman Catholicism to drunken profane rants to mumbled recitations of PC platitudes. His filmography is all over the place, ranging from hyper-violent nationalist epics to standard liberal Hollywood fare and everything in between.

Since establishing himself as creative force as director, producer and star of the Oscar-winning Braveheart in 1995, however, Gibson has been the single most powerful cultural ally of the Religious Right. Where the "God and country" salvos of the old Religious Right fell short, too heavily larded with country-western hokum, Gibson's electric freedom speech in Braveheart still rings out as a clarion call. The same God and country plus R-rated violence formula was at work in The Patriot and We Were Soldiers. He would also tackle faith more explicitly as the headliner to M. Night Shyamalan's last true hit, Signs. Each of these films foreshadowed Gibson's magnum opus, itself the single most impactful Christian contribution to culture in the 21st century: 2004's The Passion of the Christ.

It's hard to overstate how unusual the success and mass market impact of The Passion was. Not just groundbreaking as a Christian film - it racked up 15x times more box office than the most successful Christian film of the modern age at that point (the Veggie Tales Jonah movie) - it was a harbinger of the vulnerability of the media elite that had scorned the project. A gifted filmmaker with enough financial wherewithal to self-fund and some marketing savvy in reserve could make whatever kind of movie he wanted and still deliver a Hollywood-grade four-quadrant blockbuster.

The flighty Gibson did little with the domestic momentum generated by Passion, routing his immediate currency into the exotic, pre-Christian Apocalypto. The cottage cheese industry that is the Christian movie business tried to ride its coattails with The Nativity Story and Son of God with little mainstream success. Hollywood too tried a post-Christian renaissance of the Biblical epic (Ridley Scott's Exodus, Darren Aronofsky's Noah and Timur Bekmambetov's B-movie treatment of Ben-Hur) with lukewarm results. Meanwhile, Gibson was busy self-destructing, starting with his infamous 2006 DUI and its accompanying "it's the Jews!" rant, continuing with a $400 million divorce and bottoming with a disastrous break-up with his new baby mama. It wasn't until 2010 that Gibson emerged from rehab to reappear at the fringes of the culture in a series of appropriately dark starring roles.

Adding to his renewed acting efforts, he has gathered the loyal circle of film-making talent nurtured during the making of Passion and Apocalypto and is now returning in earnest to the business of cultural engagement. While violence-drenched explorations of the revenge impulse and mental illness still feature prominently, his recent work is building a strong narrative of the redemption and restoration of the disgraced American patriarch, and with him, a Christian culture.

The first entry in the Gibson renaissance was revenge thriller Edge of Darkness , playing a nothing-to-lose father seeking justice for his murdered daughter. This was followed by his starring role in The Beaver as a terminally depressed husband and father revitalized by succumbing to his driven, super-competent id, taking the form of a hand-puppet beaver. His next vehicle, 2012's Get the Gringo, represented his first return to self-funded film-making, blending the border-fixation of his earlier creative works with a renewed emphasis on rehabilitating a loose cannon into a protective and loving family man. These trends culminated with two remarkable 2016 releases that could signify his return in force to the cultural scene: Blood Father and Hacksaw Ridge.

In Blood Father, Gibson plays John Link, a trailer trash version of himself. He's a violent felonious drunk in recovery, divorced, estranged from his missing daughter, and living in the trailer/tattoo parlor somewhere out in the wastelands of the California desert. His only remaining human connection is to the local trailer trash AA group and his hick philosopher sponsor (William H. Macy, looking suitably terrible). That AA group, his higher power and the faint hope that he might one day find his daughter are all that keeps him going.

But such rawboned tenacity has a power all its own; one that, when engaged, can accomplish much more than Moore's respectability-driven media campaigns. In Blood Father, Link's wealthy, respectable ex-wife offers everything to their daughter Lydia - all the material comforts plus a fancy education - but it doesn't stop her from running away with her bandito boyfriend. Nor does the ex-wife's six-figure award bounty fetch her back. When her self-destructive behavior earns a far more effective Mexican drug cartel bounty on her, only her roughneck dad can save her. As a man with nothing to lose but the most important person in his life, he fights with a savage determination that puts the fear of God into his enemies and inspires his daughter to beat her own demons.

The Gibson-directed Hacksaw Ridge carries the redemptive arc even further, with combat medic hero Doss already having overcome his violent nature and driven explicitly by his Christian faith to save his fellows without shedding blood. Of course there's still enough blood shed to get Hacksaw Ridge Gibson's typical R-rating, which continues to serve as a dividing line between him and the ghetto of Christian niche media.

***

This time last year, Tucker Carlson was penning a far-sighted Trump piece that would pave the way for his takeover of conservative media in the wake of Trump's victory. In it he excoriated the "conservative nonprofit establishment" for their complete failure to check their ideological opponents and to understand their conservative base. They craved the respectability to impress their ideological foes in DC and purchased it at the cost of detaching from their base. He concludes that Christians flocked to Trump over his purer conservative detractors because they wanted "a bodyguard, someone to shield them from mounting (and real) threats to their freedom of speech and worship. Trump fits that role nicely, better in fact than many church-going Republicans."

Moore believes such a role should be filled by younger, hipper versions of leaders in his mold, like the young pastors he's nurtured in seminary. Indeed, he is mortally opposed to the idea of an outsider applying for the job. In his WaPo denunciation of Trump and the Religious Right, he summoned his ideal culture warrior: a "30-year-old evangelical pastor down the street from you" who would "would rather die than hand over his church directory to a politician or turn his church service into a political rally." This pastor must not "concede the public space, in our name, to heretics and hucksters and influence-peddlers."

In fact, these pastors and their predecessors have already conceded the public space and the popular culture. As Moore's example demonstrates, the only way they get access to it is by saying what their ideological foes at places like WaPo, the NY Times and the New Yorker want to hear. Without a bodyguard or a broad-shouldered fullback to punch a hole in the defensive line, there's no way to crash the party.

Moore's stated objective of confronting the culture with the strangeness of the Gospel runs directly counter to his efforts gain access to the culture by emphasizing the talking points in favor with respectable society. Jesus was a dark-skinned refugee! The illegal immigrant janitor is a future king of the universe! Donald Trump is a dirty, filthy sinner! This is not a strange and challenging Gospel but a familiar screeching refrain. It is preaching to the post-Christian choir.

Moore and culture-minded Christians would do well to compare the engagement modeled by his NY Times screed with Gibson's recent appearance on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert to promote his upcoming sequel to Passion. In stark contrast to Moore's clean-shaven Chamber of Commerce profile, Gibson shambled onto the stage looking every bit the half-crazed wildman, with soft eyes dancing manically behind a huge Old Testament beard. His personal baggage could not be more evident. He opened by bragging about a barfight with a rugby team that made him believable enough to get cast as a revenge-driven vigilante in Mad Max. Later a detour into spirituality had him seeing a devil and angel on Colbert's shoulders, with Gibson implicitly and pathetically pleading with the angel not to dig into his dirty laundry. As a public witness, to use Moore's term, Gibson is deeply compromised.

And yet there he was, in the bowels of secular pop culture, getting free media for a Christian movie centering on the boldest, strangest and most crucial tenet of the Gospel: the resurrection. This opportunity was not afforded by moral and political correctness nor abstinence from heresy, hucksterism and influence peddling. On the contrary, Gibson wallowed in the muck and mire of the worst of Hollywood and human nature, only momentarily emerging from it, like King Kong or the Creature of the Black Lagoon, to grab a hold of something pure, beautiful and redemptive. However earnestly a moral minority seeks respectability, it cannot command respect without a champion from within the immoral majority. Sometimes it takes a swamp creature to drain the swamp.

*Another example of Moore's painful naivete from Onward: fantasizing about how amazing a public witness it would be for a church to have a worship leader with Down syndrome and a scripture reader with dementia. How about an emotional equivalent of a 14-year old as president of the ERLC?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)