As Dean Abbott argues in a new essay, and I have touched on here and here, the returns on this charm offensive have been disappointing, even disastrous. Abbott breaks from the conventional wisdom that blames hypocrisy and political contamination of Christianity for its decline. It is not character deficiency but low social status that is handicapping Christian engagement efforts.

This observation rings true for me. I've long wondered why Christians are so willing to cede the moral and cultural high ground to their opponents. When you start to think of Christians as the low-status dorks of the American high school, that default position of surrender starts to make intuitive sense. When you're a teenager, no one needs to tell you that the hottie or the stud are on one tier, and that the metal-mouthed stickboy or pizza-faced shy girl are on another. You see it and sense it and adapt accordingly.

Humans are inherently hierarchical. We are constantly assessing our place in every social hierarchy. As a general rule, we even measure our happiness in terms of hierarchy. When you're working from the bottom of the sociocultural totem pole, then it doesn't matter how winsome is your messaging or how skinny is your pant leg - you are always going to be an interloper when you try to engage with anyone above you.

This concept isn't entirely new, but it has been deeply, perhaps willfully misunderstood by Christian self-critics. Russell Moore, for instance, talks a big game about embracing the low-status radical weirdness of the early church, but his bass-ackwards version of that principle is sucking up to high-status minority groups and media organs. (Meanwhile, the most effective modern Christian ministries are gathering recruits from people even lower on the totem pole, e.g. addicts in church-sponsored recovery groups)

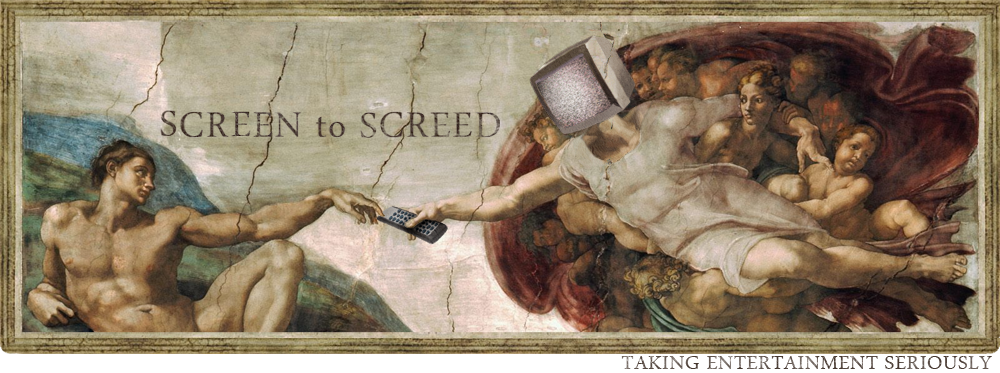

Abbott rightly criticizes the attempt of churches to become hip, a tendency that goes far deeper than the clownish efforts of guys like Carl Lentz.

|

| Nice glasses, Rev. |

Abbott stops short of specific solutions, cautiously tipping his hat towards Rod Dreher's "Benedict Option" and insisting on a realistic appraisal of our actual standing and the culture's actual problems before committing to an engagement. Having read the Benedict Option, I can offer a brief summary of Dreher's thesis: we've lost the culture war, so it's time to build a new culture by creating our own fortified institutions. Eventually the secular culture will fall to its own demons, and when chaos breaks out, the semi-monastic institutions we created will then be attractive.

That idea is particularly attractive to Rod Dreher because, like many bookish types, he has a strong aesthetic preference for medieval Christianity and an associated antipathy for all of modernity. Letting American culture collapse under its own decadence is thus an appealing strategic prospect - not only do we get to cease direct engagement with a bunch of people who hate us, but we now have civilization-saving justification for Renaissance Fair-style LARPing.

I suspect Abbott's refined aesthetic tastes - I've followed him long enough on Twitter to get deluged with Delius, Roger Scruton and the poetry I tried to leave behind in English lit class - make him more sympathetic to this approach than a pop culture hound like me. It also may have given him a blindspot in regards to the moral weight of low culture.

As High Plains Parson pointed out in his response to Abbott's essay, the loss of elite culture isn't all that big a deal in America. As he says, "America’s cultural center is more Hollywood than Opera, more hamburgers and pizza than coq au vin." But contrary to the good Parson's optimistic spin on this truth, Christians have suffered their worst defeats in the pop cultural center, which is why Abbott's low-status diagnosis rings so true.

The elites have harbored growing disdain for sincere Christianity since the Enlightenment, but just 60 years ago, Christians completely dominated the middle-brow organs and institutions that in turn dominated American culture. Blockbuster movies, TV, popular music, radio shows, local schools, councils and country clubs - all were subject to Christian approval and catered to Christian standards. Now those organs and institutions are virtually immune to Christian disapproval and most seek subversion of Christian standards as a matter of course. Though they remain central demographically, Christians have been purged from America's cultural centers of gravity.

Dreher recognizes this, but in his distaste for modernity, he essentially gives up on pop culture and focuses on small-scale regional culture. He also seems loath to deal with existing institutions, preferring to build new schools and businesses.

I believe the best way forward does not involve surrendering the power of modern mass media or washing our hands of fully-converged institutions. Neither do I want a continuation of the smiley-faced groveling of the hipster wannabes or a return to the uphill charges of the Religious Right.

The best guide for our path back to cultural influence, though they might be unwilling sherpas, is the example of American Jews. When they arrived in America, they were assigned a place on the American totem pole approximate to Christians' position today. They were generally unwelcome in the highest-status positions of society. Though they did, as I believe Dreher references, establish many of their own institutions - primary schools, hospitals, charities - and patronized their own business, they refused strictly regional limits or a ghettoized subculture. Neither did they bunker down in monastic enterprises and wait for the collapse of WASP culture. Finally, they did not engage in frontal assaults on higher-status groups.