|

| Eureka! |

Safely ensconced in a simpler age, Hitchcock observed that drama was “life with the dull bits cut out.” Clearly that is no longer the case. In this postmodern age, our lives are wrapped in so many layers of entertainment that what Hitchcock would have recognized as “life” is increasingly irrelevant as a primary source. Now more than ever, popular entertainment is our foundation, and we construct our dramas by excavating previous generation’s favorites, hammering away the duller bits to hone in on whatever was awesome about the originals. A case in point is the defining hit movie of the year thus far, Guardians of the Galaxy.

In the most intriguing, and illuminating, bit of Guardians, our ensemble of strangely familiar heroes stumbles upon the giant severed head of an ancient celestial super-being. Inside, a guy named the Collector has set up a pirate mining operation, drilling into the decaying nervous tissue, presumably to discover the wondrous secrets stored in the great old brain. The movie plays coy until the very end as to the identity of the decapitated being, when the surprise Howard the Duck cameo makes it clear (as the ever-keen Steve Sailer points out): the ancient celestial super-being is none other than George Lucas.

The Collector then is the Disney-Marvel entertainment-industrial complex, in this case represented by writer-director-foreman James Gunn, and this film is the first nugget of the box office gold that was Star Wars to be successfully refined into something shiny enough for this postmodern age. And shiny it is, gleaming like a newly-forged golden calf. Gunn has developed into a capable refiner: having earned his stripes as screenwriter on a pair of successful reboots of Boomer-era hits Scooby Doo and Dawn of the Dead, he exhibits a near perfect accord with the zeitgeist in Guardians.

Along with co-writer Nicole Perlman and the creators of the original comic (which in turn, I understand, is derivative of a Marvel universe too vast for me to comprehend), Gunn strip-mines the Star Wars universe for elements most readily recognized as “awesome,” leaving behind the less compelling bits. Guardians happily scratches the painfully earnest Luke and preachy old Obi-Wan to showcase Peter Quill, a beefed up, geeked up version of everyone’s favorite scoundrel Han Solo. Also reforged in new forms are Leia as a kung-fu fighting Green Goddess, Chewbacca as a Space Ent, R2D2 as a pissed-off tech-savvy raccoon, C3PO as a socially-awkward bodybuilder, and the Death Star as the Dark Aster. The dated Star Wars trappings have also been scrapped like so many yards of shag carpet (ironically to make way for judiciously applied retro stylings). For instance, instead of the bombastic classical scores that Star Wars made synonymous with the blockbuster epic, we get an “awesome mix” of catchy 70’s pop hits.

The resulting film is simultaneously impressive and pointless. It’s a pastiche imitating a portrait - like a Lego version of a Rockwell painting - a characteristic that is at once central to its charm and damning of its overall value. It has an unapologetic self-awareness of its derivative nature that frees it from the silly pretensions of so many other comic book adaptations. Where a movie like The Watchmen trudged grimly onward, grunting under its own importance, the lightweight Guardians lassos pop hooks with one-liners and leaps nimbly from spectacle to spectacle. All this, however, begs the question: what does it matter how skillfully the Guardians fly circles around lamer fantasy heroes? They are all still stuck orbiting the same lifeless objects, whether it be Lucas’ head or Stan Lee’s or any other misplaced centers of “expanded universes.”

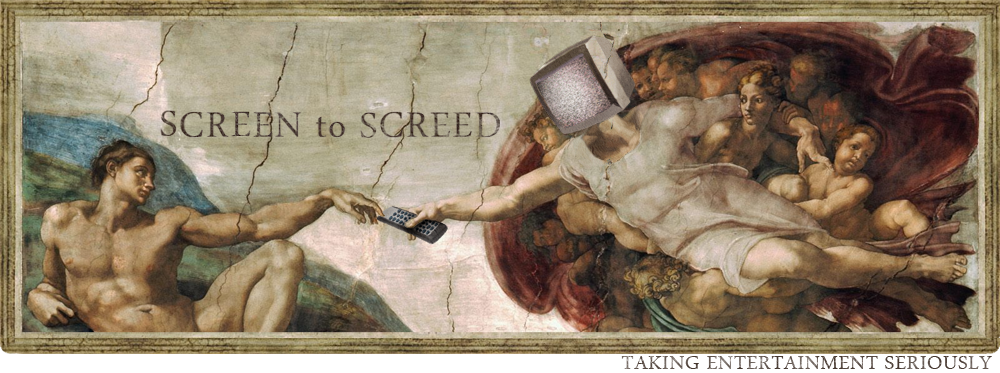

It’s not that Guardians or its lesser comic book inspired brethren are merely derivative, but that they are derivative of a derivative that renders them of so little cultural worth. Their growing popularity and sophistication is symptomatic of the broader cultural phenomenon described by the postmodern philosopher Jean Baudrillard and condemned by the Second Commandment. Baudrillard pointed to the “precession of the simulacra,” when the real is preceded (essentially replaced) by its imitation in the culture. God forbade the Jews to create graven images lest they worship them in place of him.

In the past, boondoggles like Guardians tended to be amateur projects, usually the work of adolescents and/or antisocial single guys who would expend their creative and productive energies in exploring and expanding fantasy worlds of others’ creation. Today, they attract the attention of some of our best craftsmen, the bulk of the funding of our major studios, and the brand loyalty of the broadest segment of the market. As a recovering nerd who suffers the occasional lapse, a part of me wants to embrace the success of Guardians as mainstream validation of a misspent youth. As a new father, however, I worry about the stability of a crumbling cultural foundation reinforced with Legos.